Enormous THANK YOU to everyone who signed the KY State Parks petition – Our mission is accomplished!!

Three new signs have been installed at Fort Boonesborough State Park.

See them at the Gathering of Descendants Sat. June 24

Uncovering Hidden Stories – shares research on the lives and contributions of African American settlers Dolly (enslaved by Richard Callaway), Sam (enslaved by William Twitty), Jack Hart (enslaved by Nathaniel Hart), and Monk Estill (enslaved by James Estill). Read the full narrative below.

The Fight for Kentucky – depicts the history between colonial forces and Shawnee and Cherokee tribes in the area during the late 1700s

The Transylvania Memorial – offers contemporary context for the language used on the 1935 Transylvania Monument

Background on the petition:

You may remember that in 2019 I created a petition to the KY State Parks to improve signage at Fort Boonesborough State Park to provide a culturally sensitive and accurate perspective on the historical events portrayed on what is known as the Transylvania monument, erected in 1935 by the D.A.R and the Colonial Dames. This four-sided stone and bronze monument lists the members of the March 1775 wilderness trace expedition, the members of the first legislative assembly west of the Cumberland Gap, the investors in the Transylvania Company, and commemorates the first Christian service held in what eventually became Kentucky. In my opinion, and that of many others, the language used on this monument glorifies violence and the westward movement of white supremacy and Christianity, and dehumanizes native peoples and two African American people who were on this journey.

Petition signatures along with a letter were mailed to the KY State Parks in June of 2021. By that time, two tablets from the monument had been removed due to complaints. In my letter, I requested that those tablets be re-installed and an interpretive sign be installed next to it for contemporary context. The letter also requested new signage detailing the history of native peoples in the region, and a new sign detailing recent research on early African Americans at the fort.

In 2022, KY State Parks curator Jennifer Spence developed the narrative for this sign and worked with me on some of the details and to complete the license for use of the image of the painting of Dolly. Lamont Collins, owner of Roots 101 African American Museum, commissioned the painting in 2020 from artist Audrey Menefee and I consulted with her to bring historical accuracy to the depiction.

Research from Dr. Ann Butler and others contributed to the narrative on Jack Hart and Monk Estill. The Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, The Kentucky Native American Heritage Commission, and the African American Genealogy Group of KY were consulted throughout the process.

The print and online petition from June 2019 read:

Petition to KY State Parks to create a new historical monument to be placed alongside the existing D.A.R. copper tablet monument at Fort Boonesborough State Park to update names and newly researched historical information on two members of the 1775 expedition to establish the fort, Sam and Dolly, heretofore referred to on the existing monument as “A Negro Man and A Negro Woman.”

From the Wilderness Trace to The Way Forth:

The riveting multi-generational story of Dolly and the Hart family descendants is one of the compelling narratives that inspired my compositional process in creating the folk opera “The Way Forth”. Intimate personal accounts, both of my family members and of notable women in Kentucky history, along with the evocative emotional environments that those accounts depict, are central to this musical work and the accompanying imagery and film.

One of those notable women was Dolly, one of the first African Americans to live in Kentucky. Enslaved by Colonel Richard Callaway and my ancestors in the Hoy and Callaway families, she was one of two women on an expedition party led by Colonel Daniel Boone in March of 1775. In November, Dolly gave birth to a mixed-race son named Frederick – the first child born in Fort Boonesborough. Despite her participation in this early chapter of pioneer history, Dolly was referred to only as “a Negro Woman” at the Fort monument and in the few written records from that period. I discovered elements of Dolly’s story in the recent book “Women of Boonesborough” by Harry Enoch and Anne Crabb while researching one of my own ancestors at the Fort, Elizabeth Jones Hoy Callaway.

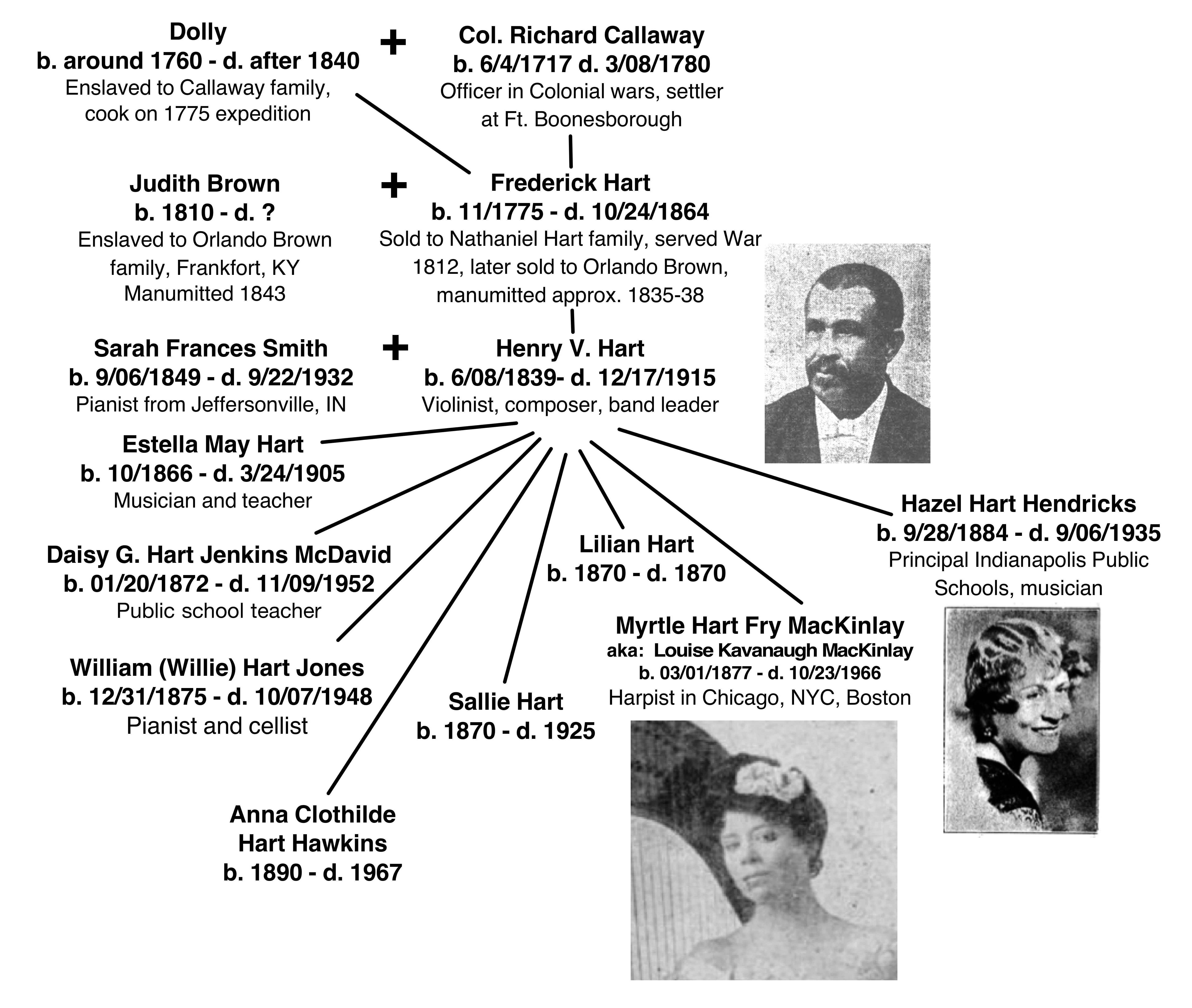

Research into these Kentucky women’s stories began in 2016 alongside the creation of the musical compositions. Even after the album recording was complete, I continued to research Dolly’s legacy. Evidence suggests that Frederick Hart, Dolly’s son, served alongside his enslaver in the War of 1812. Captain N. Hart Jr. was killed in battle in 1813. It is likely that Frederick was then purchased by Preston Brown, and later by Preston’s nephew Orlando Brown, and was manumitted in the late 1830’s. Frederick provided funds for his wife Judith Brown, also enslaved by Brown at the estate in Frankfort called Liberty Hall, to be freed in the early 1850’s. Using census records, death certificates, wills, a startling letter from 1854, and numerous other slivers and clues, I began connecting the dots between Dolly’s son Frederick Hart and his son Henry. Violinist Henry Hart and pianist Sarah Smith of Jeffersonville, Indiana married in 1866 in New Orleans, where they were playing music together in area bands. Against the imposing odds of the Reconstruction era, Henry Hart’s success as an entertainer, bandleader, performer, property owner, and published composer was boundary breaking. Over the next few decades, the Harts provided musical training for all of their daughters, and encouraged their pursuits in education and music performance. From a great-grandmother’s long life in slavery, violence, and oppression, through the grandfather’s journey from slavery to manumission to freedom, and on into many decades in education, entrepreneurship, and music, the Hart family story is uniquely and powerfully American.

Uncovering Hidden Stories – new sign narrative:

African Americans in early colonial Kentucky numbered about 16% of residents. Racism in the historical record left them invisible. They left their stories for us to rediscover generations later.

The Transylvania Company drew Whites, their enslaved, and a few free men of Color to Kentucky in 1775. They sought to create new opportunities on land purchased from the Cherokee. Richard Henderson hired Daniel Boone to cut a road from the Holsten River in Tennessee to this site. With Boone’s party were his daughter, Susannah, and at least two enslaved people.

Sam, a man enslaved by William Twitty, did not survive the journey. Native Americans killed him in an attack 15 miles from Fort Boonesborough. Dolly, the first recorded Black woman in Kentucky, endured the grueling trek. As the enslaved woman of Richard Callaway, Dolly had many responsibilities on the journey and at Boonesborough. These included cooking meals, tending fires, scraping fresh hides, and preparing pack animals. In November 1775, she gave birth to the first child born in Fort Boonesborough, a boy named Frederick. Callaway, Frederick’s likely father, sold the boy to his associate, Nathaniel Hart.

Jack, another of Hart’s enslaved men, was one of the first Blacks to reach lands south of the Kentucky River. He was present at the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in 1775. Jack served as a guide for Boone and helped construct Fort Boonesborough. He was a noted hunter and marksman. In 1782, Jack loaned his long rifle to the fight against the Shawnee and their allies at Blue Licks. The battle resulted in a rout of the militia and losing the loaned rifle. To honor Jack, the State donated a replica of his lost rifle to the Kentucky Historical Society in 2005.

Monk Estill was legendary in Fort Boonesborough and Estill’s Station. Monk arrived after the Siege of 1778. He began life as chattel property, but his enslaver’s son freed him after inheriting him. Monk was very skilled at making gunpowder and gardening, and famous for his heroics. In March 1782, he carried a wounded militiaman over 20 miles to safety after the Battle of Estill’s Defeat.

Often, African American contributions to Kentucky’s history have failed to be acknowledged. African Americans lacked basic human rights and faced peril, suffering, and death. Their perspective is essential to our understanding of the Commonwealth’s narrative and the founding of America.